A few days ago I posted a link about field notes from Christchurch archaeology to my links page for this week.

Personally I find field notes and how people use them fascinating, ever since I first managed botanists.

Full of scribbles, marginal

notes and the rest they record the progress of a survey, or an archaeological

dig in the raw, with all the gritty details, mistakes, corrections and the

rest.

And there is still a role for the field notebook/workbook/lab notebook in research, even if the final version ends up written up a little

more formally and these days electronically.

And it’s the immediacy aspect that governs the use of

notebooks.

For example, even when putting together a set

of notes for family history research, I find there’s an intermediate stage

when one writes down some rough notes and then writes them up in a more coherent

manner – probably I ought to maintain a genealogy workbook, but I’m afraid I

tend to use scrap paper and photograph any of my scrawls that are potentially

useful.

So while the lightweight research machine is excellent for

writing things up and putting things together systematically as one goes, I

find I need a rough book.

And it is the immediacy factor – it doesn’t matter too much

about the weather, one can simply pull out the rough book to write something

down.

I’ve tried using an iPad, and while they’re great for a lot

of desk based work – recording references and the like – they do need an

internet connection for a lot of applications to work.

Paper is immediate.

So, when I was documenting

Dow’s, a rough book formed part of the process.

As the various bottles and boxes contained god knows what,

and possibly in a dubious condition the use of nitrile gloves to protect one’s

hands was a given. Personally, I find it almost impossible to type even on a

full size keyboard wearing nitrile gloves, and on a smaller size keyboard well,

it just doesn’t work.

So, when examining the artefact I would write a basic

description in my rough book

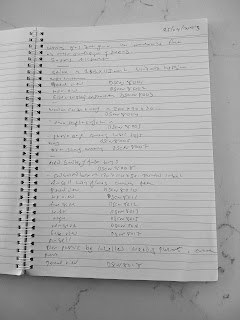

My workbook was more than usually illegible, but as I was

the only one reading it that didn’t really matter. Sometimes there were

crossings out and correction, but as the object descriptions were fairly well

structured, pages tended to follow the same layout: object: separator: object

and with aspects listed line by line.

After I’d examined and photographed the object I would

upload, review, and edit the object photographs, and then add the image names

to my rough book, before adding the object to the cataloguing spreadsheet.

This method is fairly generic, and having a rough book like

this allows you to check back on your work to make sure you havn’t miskeyed something

or missed something….

No comments:

Post a Comment